As mentioned in the broken links post, there are a lot of pages on the Lane website that are what I’d call “Resource pages”. These pages don’t necessarily provide a lot of content on their own, but have a lot of links on them to help visitors find useful resources on other pages. I’ve heard some conflicting opinions on resource pages, so I wanted to dig into if these pages are problematic, or generally helpful.

Our resource pages are often full of broken or moved links

While we’ve made some progress on how many broken or moved external links there are still thousands of broken links on the site. Because resource pages tend to be full of links to external sites, they naturally collect bad links. I’ve spent a lot of time during the last week fixing pages, and I keep coming back to resource pages, just because they have so many links.

It only takes a few bad links on a page before visitors start to wonder if the other links are any good. If I’m on a page with a couple bad links, for me it’s an immediate indicator that this page hasn’t been reviewed in a while, and I probably shouldn’t trust it.

They’re only helpful sometimes

Resource pages are usually put together out of a genuine desire to be helpful. But they’re not as well used as you might think. Here’s some data for the last year on 5 different pages I’d consider to be resource pages:

| Page | External links on page | % of external links clicked |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 17 | 47% |

| 2 | 133 | 19% |

| 3 | 27 | 19% |

| 4 | 12 | 42% |

| 5 | 25 | 52% |

At best, only about half the links on a resource page are even clicked. And sometimes, that number is a lot worse.

There’s also a whole set of people who are never even going to see your resource page. In user experience discussions, we sometimes talk about searchers (who use the search box) and browsers (who explore the site using navigation). While obviously you can be both at different times, finding a resource page as a searcher feels like a long shot to me. More likely, you’d just perform a search on Google itself and not look for anything on our site.

To me, it feels like resource pages are for browsers. People who came to the site for something else, and then stumbled on these pages and have time and interest in what was is them.

Of course, that’s just my conjecture. So I thought I’d check the data.

| Page | Views | Entrance | Exit | % Bounce |

| 1 | 774 | 30% | 27.39% | 38.2% |

| 2 | 222 | 45% | 38.74% | 60.61% |

| 3 | 93 | 5% | 5.43% | 0% |

| 4 | 78 | 5% | 17.95% | 0% |

| 5 | 410 | 14% | 11.19% | 64.29% |

This surprised me. While pages 3 and 4 certainly match my thinking, pages 1, 4, and 5 don’t. 1 and 2 actually have a higher than average entrance and bounce rates – an indicator that these pages are being found via search and attracting traffic. But the higher than average bounce rate is an indicator that we’re not retaining that lands on those pages. The people who find those links aren’t staying around.

I did a quick check on Google Webmaster Tools to see what people were searching for. Unfortunately, there weren’t enough queries listed for Pages 2 or 4 to learn much, but Page 1 stood out. There were a lot of queries referencing a specific service that actually has a page of its own, but was linked from this page. That’s a potential issue: it means that searchers aren’t finding the page they’re looking for, but instead have to land on the resource page first, then figure out what link to click.

That said, at least page 1 provided context for the links. Some resource pages are literally just collections of links, without even headers, making it very difficult for people landing on the page to find what they’re looking for.

Can hurt us in SEO

To understand this one, you’ve got to know a little bit about how Google works. This will, of course, be a gross oversimplification. If you’re interested, the wikipedia page has considerable detail.

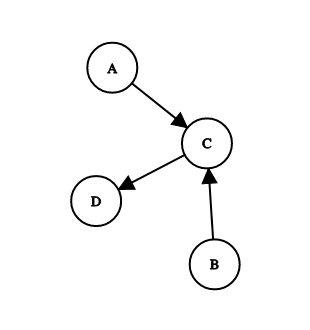

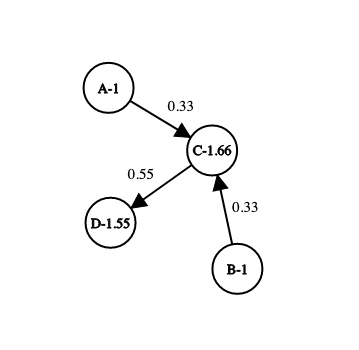

Here’s a simple directed graph:

Pretend each one of those circles is a web page, and each arrow represents a link from one page to another. Google uses those links to infer importance, and gives each page a score. If we start with each page having a score of 1, and we allow each page to transfer a third of its score to a linked page, we get something like this:

If each page has a base score of 1, and gives a third of that rank across every link, you end up with A and B keeping their scores (no one links to them), C having a score of 1.66, and D a score of 1.55. So if there’s a search, and these 4 pages are in the result set, they’ll end up with C first, and D second. Links from C are more valuable than other links, but can still be beat out by lots of low value links.

You can likely predict how people try to game this: link farming. If you get a bunch of websites to link to your page, you’ll get ranked higher. For a while, you could even pay for links to your page. Google has since adjusted their algorithm to account for that and now, if they see your page as a link farm, they’ll bump it down in the rankings. So how do they know if you’re a link farm?

We’re not entirely sure. But we think one way has to do with the ratio of outbound to inbound links – that is, links to other sites vs links to your own. If we have a page with a few dozen outbound links, like on some of our resource pages, then suddenly that ratio isn’t so good. There’s no strict rule about what that ratio should be, and since Google doesn’t publish either its actual algorithm for ranking pages, or what your score is, we can’t really know if our resource pages make Google see us as a link farm. But it’s something to keep an eye on.

You should also be alert to backlink requests. These often show up as an email, where someone will ask you to include a link to their page on your page. It’s possible that their site is actually helpful, but more likely they’re reaching out trying to capitalize on your page’s score to improve their own.

Internal resources are just as bad

Of course, that doesn’t mean you should just start packing your page full of internal links either. There are a number of pages on the site that are entirely internal link resources pages, often including an abbreviated steps to enroll or a subset of our one master resources for students page. As previously mentioned, the intent is good, but if enough people add pages like that, we’ve just added more pages for our visitors to sort through, and set up a circumstance where pages can be out of sync (that is, content doesn’t match, and we tell students potentially conflicting things). What starts out as an attempt to fix a broken navigation on our site can end up exacerbating the problem.

There’s a place for resource pages

For instance, here’s a budget page. If I do an analysis like with the pages above, the numbers will look terrible. And this page definitely doesn’t provide any links in context. And compared to some of our pages, I can’t imagine it gets a lot of traffic. But that isn’t the point. This page gets used a lot in the budget planning cycle, as emails and presentations refer people to this site as a place to find specific resources. While it may be one of the most plain pages on the site, the headers make it quite functional. Sometimes a resource page is the right choice.

So what’s the conclusion?

As with anything else complicated, it depends. There’s a place for resource pages, but if you’re thinking about putting one together, you should think long and hard about if that’s the best solution. For instance, if you’re putting that page together because you genuinely think it’s important students learn about each of those links, you might be better off communicating a few resources every so often with a targeted population, or regularly posting resources to social media, or you might be better off working resources into each of your other pages, surrounded by related content.

If you absolutely must have a resources page, then make certain to put some context with the links, so that page visitors know why you’re bothering to put this link on a page. Be sure to revisit your links once in a while, and fix any broken or moved ones. And watch out for backlink requests!

If you have a page and you’d like to know if it’s working, reach out! We can dig into how people are finding it, what they’re clicking on, and if they go on to other pages.