It’s fairly well accepted that it’s important to have a super fast webpage. We’ve spent much of the last two weeks working on our back end design to make the new Lane webpage as fast as it can possibly be. This blog post will be about sharing our results. A few notes before we begin:

- These tests were conducted mostly on my own laptop, which was busily doing other things, so results aren’t scientific – but it’s good enough for the type of basic improvements we’re going here. On the plus side, this will totally eliminate network effects, since there isn’t really a network.

- We’ll be testing on the development version of our contact page at http://www.lanecc.edu/contact

- Some of these improvements are technically still in testing, and thus you won’t see on the main website (yet). Others were actually implemented weeks ago, but I’m rehashing them here because they’re some of the simplest improvements you can make.

- I’ll be using Firebug to watch the event timeline to see how long things took. This isn’t perfectly accurate, but it’s pretty good for us. And Firebug is amazing.

Baseline

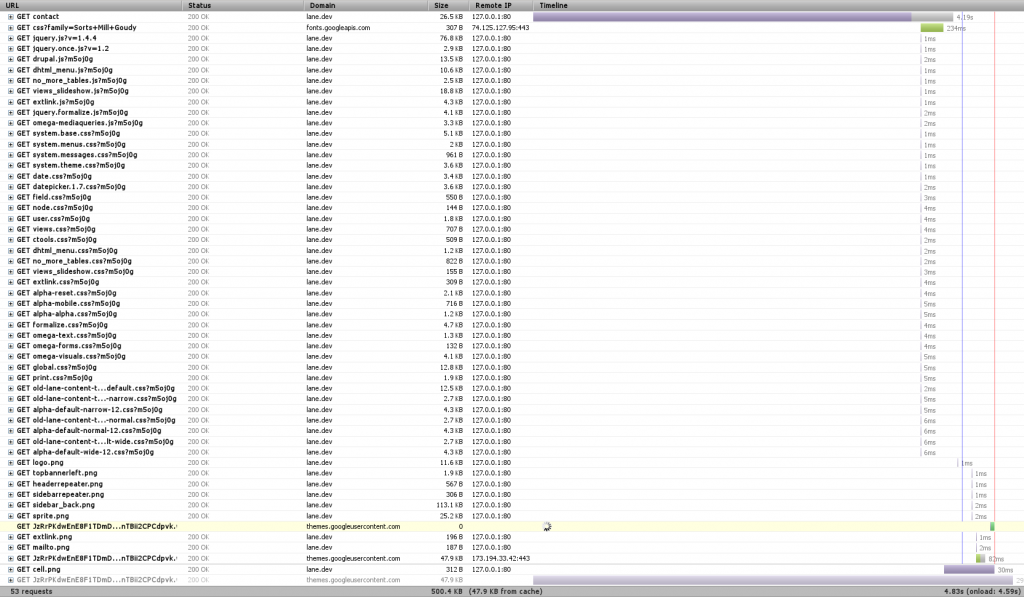

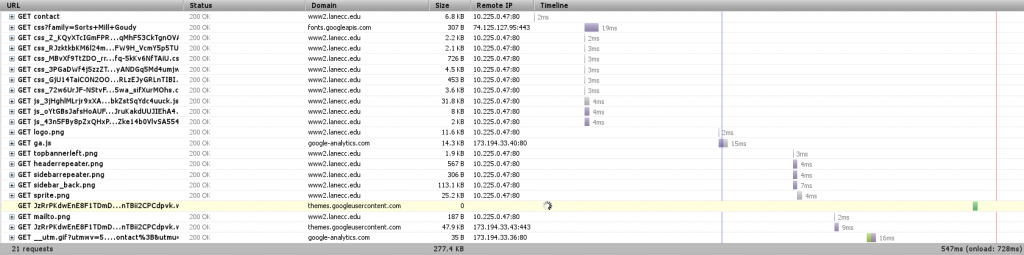

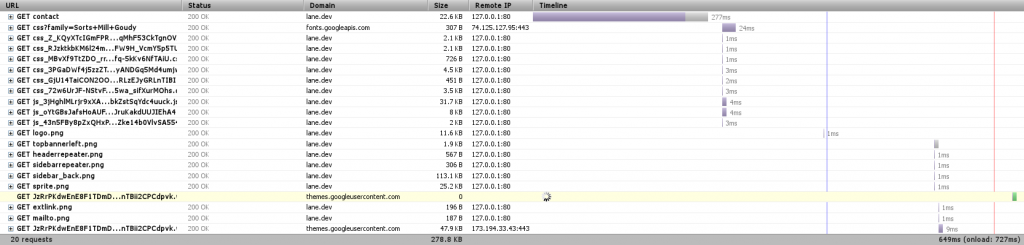

In any testing, you need a baseline. Here’s the timeline for loading the contact page (remember to click on any image to see the full size):

Right away we notice three things – first, that there’s a font that hasn’t finished loading, and which is highlighted in yellow toward the bottom. That’s actually an issue with Firebug, so we can just ignore it.

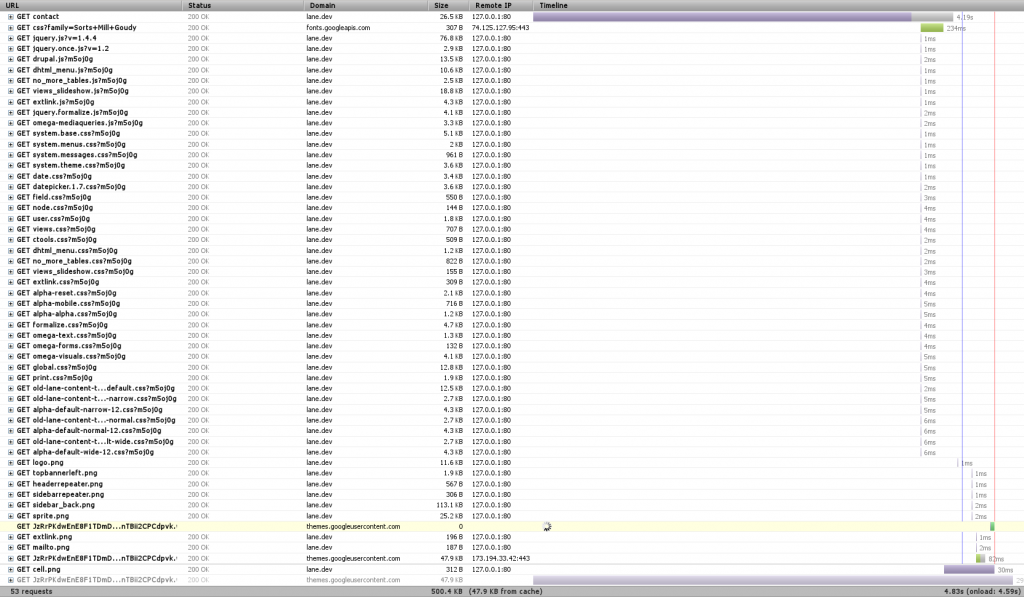

We also notice that there’s a TON of requests. In this case, 53 (technically 52, since we’re ignoring the font one). When we’re dealing with a local server like this, each of those requests happens super fast. But when we’re dealing with a remote server, like with 99.999% of web requests, there’s a limit of how many requests you can make at one time – always less than 10. So we can get a significant speed boost if we combine requests (You can see some of that limit at the bottom of this post).

Finally, we see a huge purple bar up at top. Any time you see purple in Firebug, that’s when we’re waiting on the server to do something. In this case, we can see that it took about 4 seconds for Drupal to render the page. Surely we can do better!

CSS/JS Aggregation

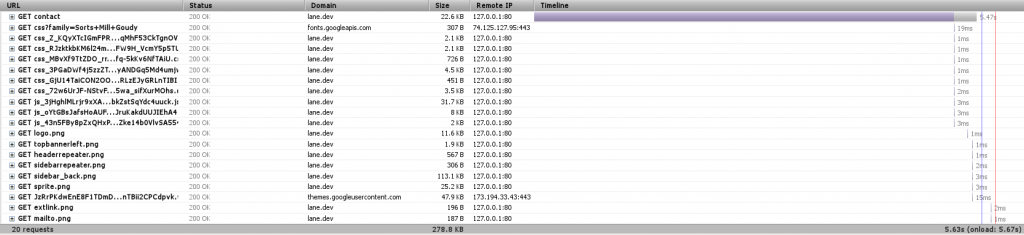

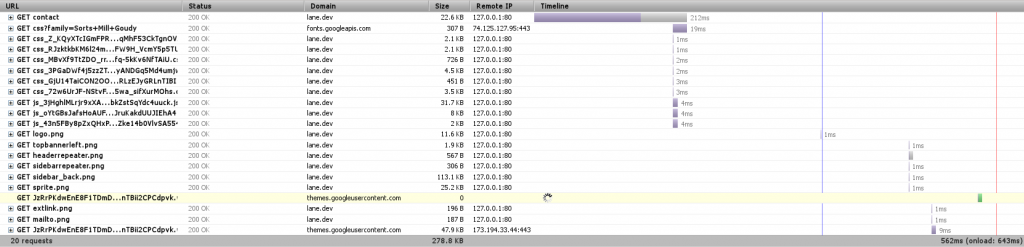

Our first step will be to combine CSS and Javascript files. We won’t see much of a difference on our tests (things might actually get worse!), but we’ll see a significant improvement on the actual site.

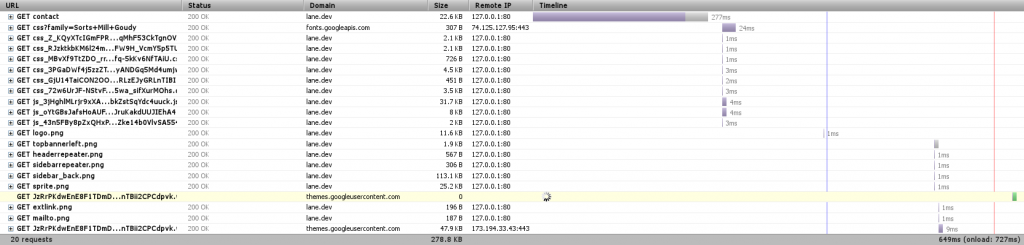

We’re down to 20 requests, just by telling Drupal to combine JavaScript and CSS files where it can. Eliminating 30 requests is actually a significant speedup (Sorry I can’t easily show it here, but you can see other research online).

Also worth noting is the file ‘sprite.png’ that’s listed on there. This is essentially the same idea, applied to images. You can look at our sprite here.

Medium Level: APC

We’re going to skip over the next most obvious method of speeding things up and instead have a look at the Alternative PHP Cache (APC). Drupal is written in PHP, which is an interpreted language. That means that when we process the index.php file, we first turn it from normal PHP code to optcode, which is then run on the PHP virtual machine. APC lets us store (cache) optcode, so that we can skip that first, interpreting step.

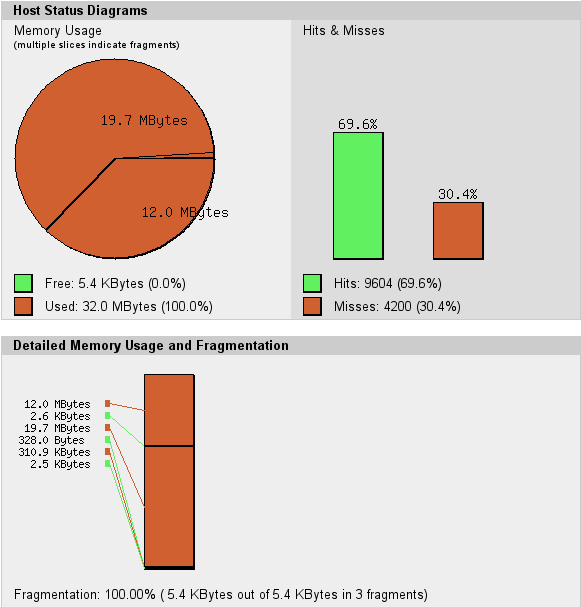

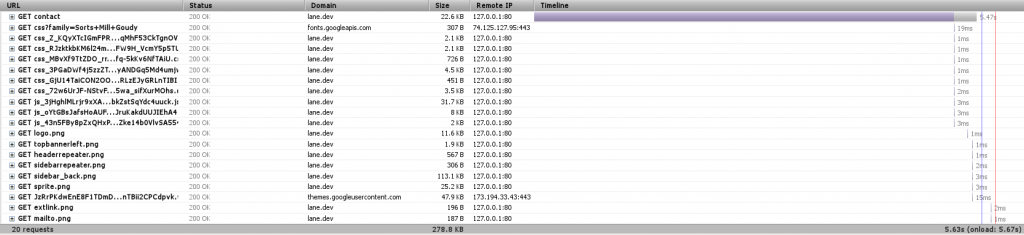

The other night, we found that our server was actually freezing on some requests. We had a look at the apc cache, and we found something like this:

The circle is all red – there’s no more free memory available for APC to use to cache optcode. Our memory is also fragmented – APC can’t keep things near each other, which is going to make the cache work harder than it should. Together, these two things make us ‘miss’ the cache – on my computer, there were 4200 opportunities to speed things up that we missed. So we simply increased the cache size.

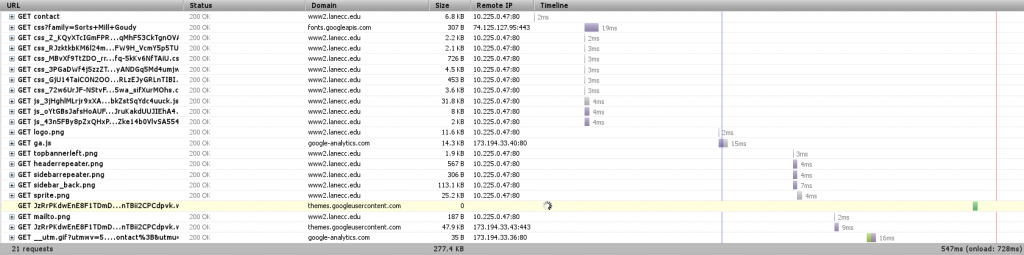

Now we’re loading the entire page in 640ms, and it’s only taking Drupal 277ms to get us the page content – less than 1% of the time it took before.

Medium Level: MySQL Caching

The other place to do caching is our database. Some types of requests to the database are really simple, repetitive things that could easily be stored in memory instead of on disk. MySQL provides a query cache where it learns what those things are. By default, this cache is turned off. If we turn it back on:

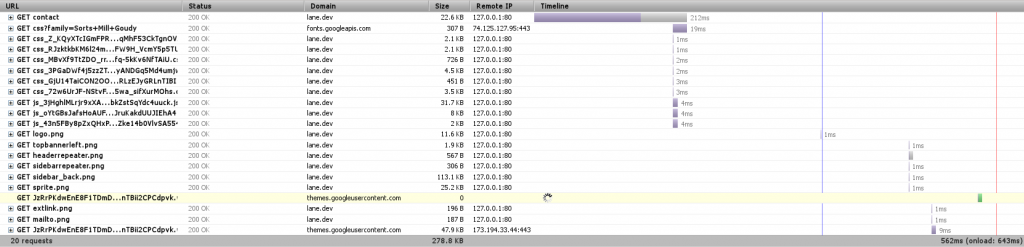

Now Drupal is able to get us that page in 212 ms – almost 25% faster.

Now what?

So we’re pretty quick. But, being programmers, we’re never satisfied. On our actual server we’re also:

- Minifying additional JavaScript & CSS

- Tuning our Web Server parameters so that we always have something waiting for your web page request

- Pushing some resources onto a Content Delivery Network (videos, fonts, some JavaScript), so that they’re shared between multiple websites, reducing the likelihood you’ll need to download them.

- Running much JavaScript from the bottom of the page instead of the head, so that the page will render in your browser before doing Javascript – giving the appearance of it being faster.

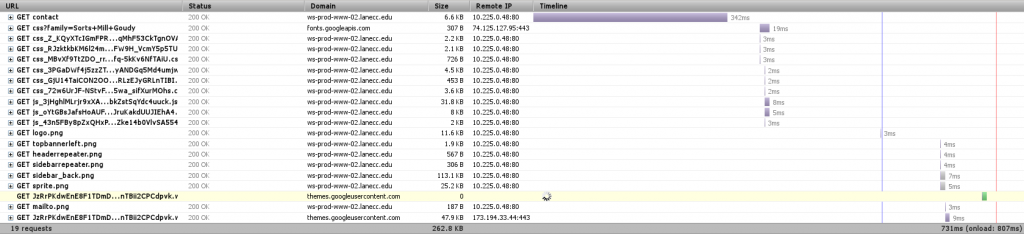

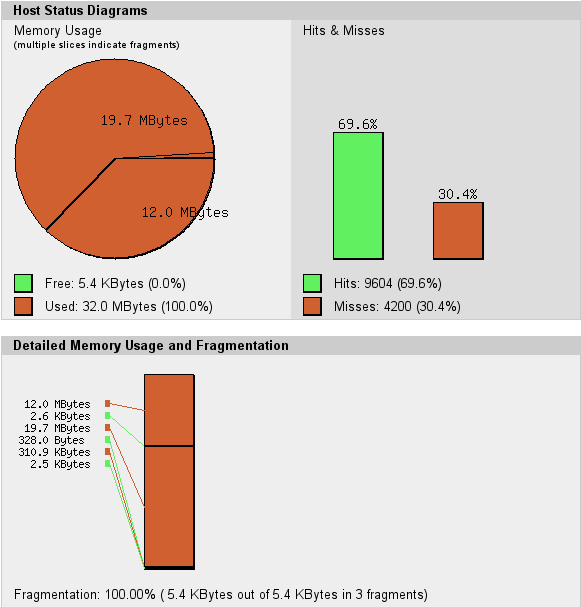

Here’s the timeline from the actual server to my computer, as it is right now:

But there’s one more big thing we can do.

Anonymous User Caching

When Drupal renders a page, it needs to fetch information from the database, process a bunch of templates, check user permissions on a ton of objects, and then build the page. Then Apache, our web server, needs to serve that page to you. Apache is a good web server, but it’s a general purpose web server, designed to serve many different languages. There are faster alternatives.

We currently have a server in testing which is designed from the ground up to serve pages as fast as it possible. Pages loaded from that look like this:

Our Varnish server is an entire separate server that sites between you and Drupal and does nothing but determine what pages could be stored in RAM as complete pages, ready and waiting for when you want them. In this case, it was able to return the contact page to me in 2ms – most of the rest of the time was spent waiting for other resources – CSS, Javascript, and fonts – to load. Now it’s obvious why reducing the number of HTTP requests would speed up our page load – those bottom requests would be made sooner.

Varnish posed a special problem for us these last two months while we were testing it. First, it doesn’t do encrypted traffic. For that we have a separate nginx server, which takes care of passing your encrypted requests straight to Drupal. But our second, more fun problem was figuring out how to load test Varnish. My laptop wasn’t strong enough, then our other web server wasn’t strong enough, and then a set of 5 other machines on the same network weren’t strong enough. Varnish was able to handle thousands of requests per second, and not even blink.

Finally

Thanks for sticking with me this long! Except a much faster web site before the end of the month, as we finally turn on Varnish for the rest of the world. And we know there’s still work to be done. Our next design should feature fewer requests and less JavaScript, letting your page load and render just a little bit faster.