This month I have written up quite a few digital text, some of which I’ve posted on this blog, some of which is emails and other documents, some of which is on my LMS.

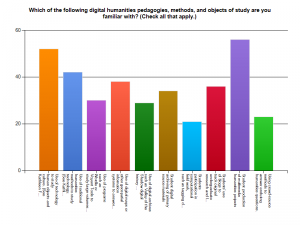

I created a Survey Monkey survey here that has lots of words and got lots of responses. ; )

Been Stewing on the Goals of Digital Literacies–a Zero-Sum Game with Older Forms?

For the past eighteen months or so a dear friend and fellow Buffalo grad school alum and I have been having an extended sporadic conversation about the value of blogs, tweets, facebook, digital tools in general for teaching community college students literature and composition. Yesterday in our most recent conversation, she and I came to a new place in this conversation. [this continues the topic of my first blog post on this blog which engages with Mark Sample’s idea that “serial concentration is deep concentration.”]

How to Help 21st Century Students See the Value of their Own Contributions in a Global Sea of Information

We started by talking about plagiarism, and I shared with her the recent conversation I had with a student about an assignment I’d given. I’d asked my Women Writers students to go to Poets.org’s poetry map and produce a mini-research blog entry on the state of poetry in one of the states on the map, with particular attention to women poets. One student said to me, “But why do you want me to write about this—someone already has and it’s already on the site.” I smiled and said that yes, someone has given her some information about the poetry scene in the state of Iowa, and listed six male poets and perhaps one female poet in that state. Her job was to read the site and follow the links and come to some conclusions about our course thesis which extends Virginia Woolf’s in A Room of One’s Own. A lightbulb went on at that point as this student realized that she had something to contribute that went beyond the reports on the site: that she could in fact be a critic of the site in the way that Woolf is a critic of English literary history.

Back to my conversation with my friend: I told her how this student’s response to Poets.org was new, something that we didn’t share when we were in college and grad school. To my student, if information was already “out there” and freely available, then why would she take the time to summarize that information? Something that had been a cornerstone of our education—to do literature reviews and demonstrate everything that we’d read and retained—had been outsourced to the cloud and the web, in this student’s view. This student only saw value in the assignment when she understood how she was being asked to actively manipulate it. The value that we hold for summary was elusive to her. During the DH lab, I explained to her that the Poets.org info was up there, but it was up to her not only to summarize what was there but to summarize in the service of understanding and evaluation. For example, there was one state in Poets.org where only one female poet was featured. What did she think about this? Did she really think there was only one female poet in that state? How did what Virginia Woolf tells us in Room of One’s Own pertain to this fact? These are the questions that she was being asked. After this explanation, the student came up with a very strong blog post.

My Buffalo alum friend and I continued our conversation about plagiarism, and I told her that in some ways I have found that digital engagement, while on the one hand encouraging cutting and pasting wholesale can also encourage a kind of manipulation and sense of entitlement to the text that fosters creative and critical thinking.

We talked quite a bit about the role of the traditional literary essay in my lit class, and I said that none of my assignments fit that form, and yet I felt that my students were achieving the outcomes set out in the course, and also some other outcomes that aren’t explicit in the course syllabus—namely, collaborative problem-solving and document production; some basic digital literacy skills such as signing up for accounts and maintaining their passwords, posting and revision online.

We continued the conversation later, and started talking about the value of the sustained analysis involved in writing a literary analysis paper, the importance of the form, etc. And then we thought about the form of the lengthy, sustained analysis paper, and we allowed ourselves to imagine for a moment that maybe the sustained concentration involved in writing a literary analysis paper is perhaps a fiction after all. That perhaps a literary analysis paper, like the kinds of projects that we are talking about in our DH labs, is actually serial concentration too—and what is actually sustained is the paper itself, strung together in an artifact that is labeled as a single, continuous whole. But when you really think about it, any lengthy essay is put together through serial concentration: finding quotes, taking notes, stops and starts and fits of production and writer’s block. Perhaps the only sustained concentration involved in many of the traditional essays that we’ve been requiring for decades is the ½ hour of focus that the teacher spends in grading it.

Of course, many students may in fact spend several hours focused on writing a final paper, and I know that I did while writing my dissertation. But some of the projects that we’re working on in the DH lab take a different kind of deep concentration.

Fun Home by Alison Bechdel

Yesterday’s class we engaged with Fun Home by Alison Bechdel for the last time of the term. I began by showing students Scott McCloud’s dense and quick (too dense? Too quick?) TED talk on Understanding Comics. There is much to be mined from his talk, and next time I use it I think I’ll use it with at least parts of the book as well. Since this is a women writer’s class, though, I only wanted to give students a quick intro to the many stylistic/generic features of Bechdel’s work and the work of comic artists in general. What I really liked about McCloud’s piece is that it very efficiently set the stage for establishing the comic/graphic novel form as an art form with deep historical roots, as worthy of serious inquiry and analysis as Bronte or Dickinson or Woolf’s written forms.

For the next time I teach it, I’d really like to figure a way to use the graphic organizers that McCloud introduces as a way to graphically engage with Bechdel. Even in the short time we had, students were able to identify segments or features of Bechdel’s work that drew on Classicist, Formalist, Animist and Iconoclast values.

Figuring out how to feature this in a DH context is my next challenge. I think it may involve using some form of free cartooning software, and perhaps thinking about McCloud’s discussion of how comic artists create forms that represent something essential about a character or moment in time. I also like how he talks about time and space in comics—this could be something that a timeline could be used for. Or maybe his discussion of abstraction and representation. I’m not sure yet, but I’m sure that for the next time we can perhaps work out a way that students can create a comic strip—maybe a few panels—out of what we’ve read earlier in the term using some of McCloud’s discussion and Bechdel as a “monstration.” Hmmm….NCTE has this resource or Mashable’s list. I’ll have to check back next time around. I do think that students can get some of the feel for the “classicist/formalist/animist/iconoclast” forms by creating a few panels of their own—they might even be able to discover which style they lean toward….