Text from MLA 2017 Talk on DH Forum “Minimal Digital Humanities: Choice or Necessity?”

This paper engages with Jentery Sayers’ and Alex GIl’s discussion of Minimal Computing on

In April, I will teach what I believe will be the first stand-alone Intro to Digital Humanities course at a community college (CC) in the Pacific Northwest—maybe the first such course at a CC in the country. I call my course “This Digital Life: Reading, Writing and Culture in a Digital Age,” because my students don’t know what “digital humanities” is.[i]

In this course, I will introduce my CC students to a way of thinking about and comprehending the forces around them—the forces that Alan Liu calls the “great postindustrial, neoliberal, corporate and global flows of information and capital” (Liu 491). Community college students’ lives are immersed in precarity wrought by these flows; only the grittiest of them will overcome the bleak economic for economic mobility in America. Articulating how those forces affect them is one of the most important learning outcomes of DH at the CC.

But what are the minimal computing coordinates for CC students? And where does open source fit in an open access environment? I hadn’t really thought of this before reading Alex Gil’s and Jentery Sayers’ definitions of “minimal computing;” I am unsure how to use Raspberry Pi and I can barely work with Markdown templates. I do use whatever tools are available and we’ll read whatever open educational resources we can find. Perhaps, following Gil and Ernesto Oroza, my community college DH course will follow a kind of “architecture of necessity.”

While the surface features of my course are not strictly “minimal,” they share structural affinities to the GO::DH values of maximum access and longevity: My students might read Gil’s and Sayer’s pieces but they will likely write about them using Google or Word on their laptops and email me using Outlook—transgressing minimal computing principles at every keystroke. I think that these definitions of minimal computing themselves point to a set of assumptions for humanistic computing that are worth considering in CC students’ digital lives.

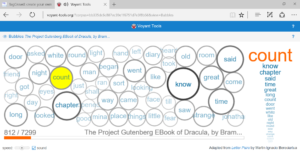

I’ve practiced not “minimal” computing but what Roopika Risam calls “micro DH.” Since 2012, I have embedded whatever I could invent or learn in all my courses, adopting and adapting from a generous DH Pedagogy Community and translating research so that my students can appreciate the cool factor of big data without slamming up against skill barriers to data mining; and then I send students to Wordle or Voyant so they can work the magic themselves. My students dive into archives and annotate texts using Google docs. Sometimes we “break” Google or Twitter because our computer lab is equipped with lame machines and the systems crash. The Computer Help Desk folks are so used to hearing from me about glitches during class that they respond immediately when I call; if I ever have a classroom emergency, it’s them I’ll call first, not campus security.

Reconsiderations and a Maturing Field

While minimal computing intends to create conditions for maximum inclusiveness, I fear that in practice it may exclude underprepared students in open-access institutions.

The minimalist turn registers the effects of uneven development in the academy. Community colleges are just beginning to recognize the term “digital humanities,” and faculty are just beginning to figure out how digital assignments fit into their courses. In many, although not all, cases, “minimal computing” assignments take maximal preparation–for CC faculty still untrained in the field and for unevenly prepared students.

Jentery anticipates the critique that minimal computing may produce different impacts to different agents in an unevenly developing field. He asks, “what sort of expertise and decision-making [does minimization assume]” and how do “we define ‘we’ in relation to necessity and simplicity?” (“Minimal Definitions”). Necessary for what? Simple for whom? Under what constraints?

For community colleges, the purpose of humanities education is to empower students with as much mastery of as many tools as possible for full participation in civic and cultural life. How we define “minimal computing” at the CC needs to support that purpose.

For I’m not just talking about access to any particular set of digital tools—whether “minimal” or “maximal”–in this regard. Rather, it’s students’ transformed understanding that I am after—the crossing of a threshold from accepting a received cultural landscape to a deep reading of it. Open-access institutions may make use of “maximal” tools as a relay for critically engaging with the digital life they lead. In so doing, they may achieve ends that “minimal computing” principles intend.

Participation, writes Carpentier, is “strongly related to the power logics of decision making” (8). Carpentier’s foregrounding of power relations and social capital helps us to situate values of minimal computing in an open-access CC context. Looking at Jentery’s comprehensive list of the features of minimal computing, we see that he is going for a maximalist model of participation in stewardship of the cultural record and in knowledge production and dissemination. The list helps elaborate the question that Alex Gil asks—that of “what do we need?” –and imagines a DH architecture of necessity that ensures scholars’ maximal role in decisions and maximal control of future use.

While community colleges share disciplinary affinities with their counterparts at 4-year colleges and universities, these affinities mask power differentials between CCs and their four-year counterparts. Carpentier’s focus on power provides language for recognizing the differences between four-year institutions and CCs and for responding to those differences.[ii] This power differential is visible in multiple spheres, but here are a couple of examples to illustrate how it impacts faculty and students at CCs: [slide 1]

- First, graduate school doesn’t train most humanities graduates for the demands of CC teaching

- Second, graduate faculty rarely maintain close professional ties with students who land jobs at CCs. I call this the “You’re dead to me” model of mentorship.

- Effects of this dynamic on professional development have been to create an hermetic CC professional world cut off in important ways from developments in the larger field

- This dynamic limited what should have been a much earlier diffusion of digital humanities methods into CC curricula.[iii]

Additionally, the role that contingency and precarity play in CC faculty lives cannot be overstated. Part-time/adjunct faculty represent nearly 70% of the instructional workforce of community colleges and 47% of humanities educators overall (“A National Survey” and “Traditional versus Nontraditional Humanities Faculty”). Many part-time or adjunct humanities faculty teach given syllabi or are limited in the texts they can select. Maximal equity in participatory decision-making in curriculum is harder for contingent faculty to achieve.

And what about CC students?

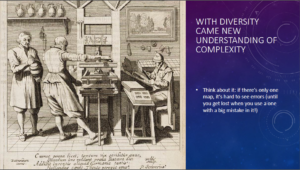

What might minimal computing look like for them and how might they practice it? Student diversity is the open access institution’s best asset and biggest challenge. [1] Jentery raises the issue of time in relation to reduced consumption (“Minimal Definitions”); working class time orientation is characterized by “precarity”—a sense that struggles in and endurance of the present are more salient than investments in a future imaginary. You could say that CC priorities are driven by a working class time orientation toward the “short now” and not the “long now” thinking required of the minimal critical movement (“Minimal Definitions”).

How else might “minimal” computing impact students’ full participation? “Creative failure” and “generative messing around” may directly challenge an already profound sense of what Walton and Cohen call “belonging uncertainty.” Experiences of failure that middle-class students may simply slough off disparately impact minority students’ sense of belonging and social “fit” in college. CC students are already “doing the risky thing” (Fitzpatrick)—they’re going to college. Trial—and especially error–around spartan and user-unfriendly interfaces can challenge even the most confident of lifelong learners. Recently, I fell short of completing a Github pull request after many tries, and I had the humbling experience of standing on the wrong side of a threshold. Perhaps for CC students, commercial interfaces are the “architecture of necessity” (Gil)– the best way to ensure that they cross important thresholds when taking on digital projects.

When I was reading about minimal computing, the words “syntactic sugar” and “syntactic salt” popped up. This language of low-processing and elemental design pepper minimal computing definitions and put me in mind of the language of food politics–Whole Foods, organic produce, farmers’ markets and distributed pantry movements. Why is it, I wondered, that the advantages of bypassing the supermarket to ensure maximal autonomy are only realized by middle-class families with huge domestic square-footage and mini-vans? Do the conflicting urgencies of class and environment operate in minimal computing?

If they do, what kind of computing can help CC students comprehend and intervene in the high-speed, overprocessed environment of their “digital life”? Thinking of supermarkets led me to consider how McDonald’s, Burger King, Taco Bell and KFC leverage food deserts for profit. I looked up the Food Desert locator data visualization map posted by the USDA [Figure 1 “Food Desert Map”], and then quickly also found the Fast Food restaurant map [Figure 2 “Fast Food Locator”]. Then I went back to the GO::DH map that locates DH centers globally [Figure 3 “In a Rich Man’s World: Global DH”] and created my own DH at the CC data viz map using Google Maps to see what it might reveal. This was networked computing toward a local end [Figure 4 “The Only CC Digital Humanities Faculty in the PacNW Flies to the MLA”].

So I’m saying that “maximum” computing can serve “minimal computing” ends of inclusiveness and participation, but I do know I need to avoid creating conditions for CCs to become digital equivalents of food deserts. A sole diet of Google, Microsoft, Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, Snapchat et al. could play into a lifetime of dependence on overprocessed commercial platforms. Meanwhile CC students’ four-year counterparts at Honors Colleges and First Year Interest Groups tinker with their Tiny Linuxes, “healthy choices” and “whole foods” of Raspberry Pi. But for now, that’s where my staircase ends.

[1] CC Student facts: There are 992 public community colleges in the US, and community college students make up 46% of all undergraduates in the US and 41% of all first-time freshmen. Sixty-one percent of Native American college undergraduates are enrolled in community colleges; 52% of Black students and 43% of Asian/Pacific Islander undergraduates are enrolled in community colleges; 50% of Hispanic college students begin at community college. In the US, 59% of community college students are enrolled part-time, and 59% are women (American Association of Community Colleges, “Enrollments”). The SES data on CC students are well known (Adelman): 44% percent of low-income students attend community colleges as their first college out of high school as compared to 15% of high-income students (Community College Research Center). Sixty-nine percent of community college students work, with 33% working more than 35 hours per week; 22% are full-time students employed full-time; 40% are full time students employed part-time; and 41% of part-time students are employed full-time. And first-generation students make up 36% of community college student populations (American Association of Community Colleges, “Fast Fact Sheet”).

[i] I should have heeded Ryan Cordell’s advice about course naming http://ryancordell.org/teaching/how-not-to-teach-digital-humanities/

[ii] I want to acknowledge here the existence of many under-resourced four-year colleges and universities as well, and that we are talking about a complex system of power and privilege operating in higher education. But CCs have an open-access mission and a lower-division or foundational focus, and this puts them at a singular disadvantage in terms of social capital—for students, for faculty within the profession.

[iii] There are some hopeful signs on the horizon in this regard: The University of Washington and CUNY Graduate Center have explicitly engaged with community colleges as a site for expanding public humanities, but the impacts of these initiatives remain to be seen.